George Ritchie Hodgson (October 12, 1893 – May 1, 1983) is considered by many to be the greatest Canadian swimmer of all time. Extremely modest, he rarely spoke of his achievements that included numerous world records and two gold medals at the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm.

Take a journey through his life as told by the many news articles collected over time by his family as well as artifacts donated to the Canadian Aquatic Hall of Fame.

1910

Born October 12, 1893 in Montreal, Quebec, George Hodgson first learned to swim at various summer resorts in the Laurentian Mountain Lakes.

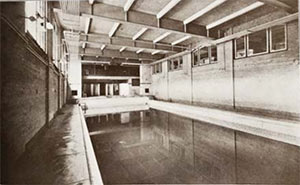

He later attended the High School of Montreal where he was a frequent visitor to the Montreal Amateur Athletes Association (MAAA) clubhouse which had one of the few indoor pools in Canada. It was there he came under the guidance of Jimmy Rose, the club’s swimming instructor. Click on the image of the pool to see a larger version.

Early competitions

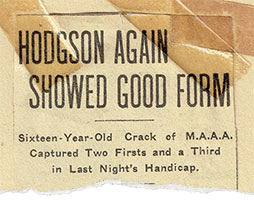

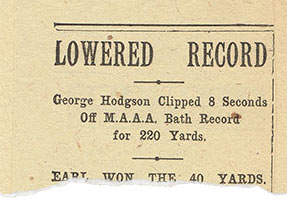

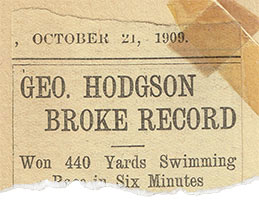

As a team member of the Montreal Amateur Athletes Association, he would compete in the weekly swim meets held at the facility and swam to victory in many events. Many of these swims were documented by the local newspapers and collected by his mother for his scrapbook.

Click on the thumbnail images to view an early photo of Hodgson and some of the 1909-1910 news articles from George’s personal scrapbook:

1910 Canadian Swimming Championships

In August 2010, Hodgson swam at the Canadian Swimming Championships held in Toronto, where it was reported that the “crack MAAA swimmer was the hero at the swimming championships… [who] captured the quarter mile race, in somewhat easy fashion, going the distance in the fine time of five minutes and fifty-nine seconds”. Click the thumbnail (right) to view a news article covering the quarter mile race.

In August 2010, Hodgson swam at the Canadian Swimming Championships held in Toronto, where it was reported that the “crack MAAA swimmer was the hero at the swimming championships… [who] captured the quarter mile race, in somewhat easy fashion, going the distance in the fine time of five minutes and fifty-nine seconds”. Click the thumbnail (right) to view a news article covering the quarter mile race.

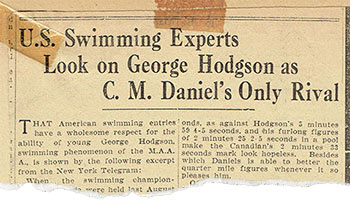

It was such a victory that some asserted the course must have been short, although fellow competitor “Bud” Goodwin of the New York Athletics Club “made the prophecy that before another year had passed the Canadian youth would be hard on [American swimmer] Daniels’ trail.” Click the thumbnail (left) to read the full American newspaper article on the remarks.

At the same swim meet, Hodgson also broke the Canadian indoor swimming records for the 100 and 220 yards. Click the thumbnails below to view Hodgon’s 100 yard trophy and a newspaper article about the wins.

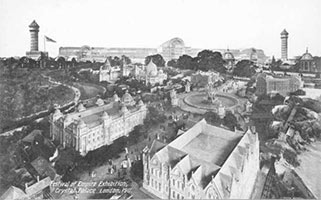

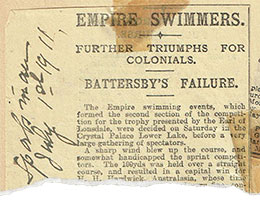

1911 Intra-Empire Championships in London, England

Undefeated in Canadian and U.S. competitions to this point, he travelled to Crystal Palace, London, England to compete in the Intra-Empire Championships at the Festival of the Empire – considered to be the birth of the British Empire Games.

Canadian team manager Norton Crowe asked Hodgson his best time for the mile, who replied “I don’t know, I never swam one”. He would later recall in a news article, “There were no lanes and no lines on the pool bottom to guide the swimmers. They placed a log boom across one end and you turned on that”. Not only did he win the mile, he also broke the world record with a time of 25’ 27” .25. Click the thumbnails below to view a games photograph (source: unknown) as well as articles on George Hodgson’s mile including his splits for the race.

Upon his return home, Hodgson stayed in Montreal just long enough for a swim at the MAAA before departing for his parent’s summer house in Ste. Agathe for a short rest before resuming competitions.

According to many at the time, Hodgson was an extremely modest man about his achievements to date, and had said very little about performances. One reporter commented that it was “becoming a pet grievance with his friends that he refused to discuss his experiences in England at all”. He would later swim in the Canadian Championships taking place in late July and August in Valois, Halifax and Ottawa, before leaving for New York for the American Championships.

More wins with an evolving swim technique

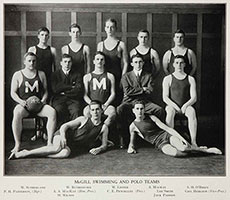

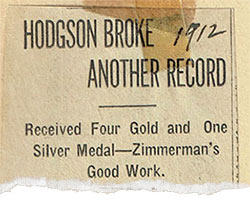

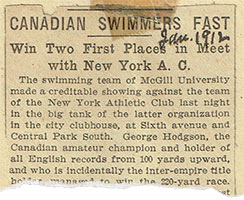

After returning home from the Intra-Empire Championships, Hodgson continued swimming with a string of successes, winning all of his events at the Canadian Indoor Swimming Championships in early 1912 and, after acceptance to McGill University, helping their swim club win the Inter-collegiate swimming championships. Contrary to the legend that he had never lost a race, his only losses occurred in a meet in New York where he was defeated in two separate 100 yard races, including once in a tight finish by N. F. Nerich from the New York Athletic Club during a duel meet with McGill. Hodgson did win the 220 yard race at that meet, finishing within three seconds of the U.S.’s Charles M. Daniel’s record. Click on the thumbnails below to view the newspaper articles covering the races.

It was during this period that Hodgson worked hardest with Rose to prepare for the Stockholm Games. They worked as brothers; Hodgson putting his heart and soul into his training. He became less satisfied with beating competitors or making good times; he was out to improve himself. The young swimmer proved easy to coach, always willing to try any experiments to better his time, always appreciative of suggestions which could help him improve. He was a model athlete to train, working hard to perfect his new style. Click on the thumbnails below to view the newspaper articles covering his evolving stroke and the controversies surrounding it.

Olympic Trials

Hodgson competed in the Swimming and Diving Elimination Trials at the Montreal AAA clubhouse that took place May 31-June 1, 1912 to determine who would compete at the Olympic Games in Stockholm later that month. George won both of his competitions, defeating Montreal AAA (MAAA) clubhouse teammates Frank McGill and George Draper in the 100 yds free style in at time of 58 2/5th as well as M.A.A.A.’s J. Caines and Montreal Swim Club’s M. Ross to win the 410 yds free style with a time of 5:40. Clikc on the article below as well as the Olympic Trials program with George Hodgson’s events.

1912 Olympics

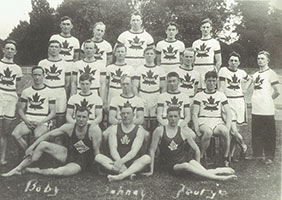

After months of preparations Hodgson traveled to Stockholm, Sweden with his teammates for the 1912 Olympics. Click on the thumbnail (right) to view the team – Hodgson is bottom row, far right.

After months of preparations Hodgson traveled to Stockholm, Sweden with his teammates for the 1912 Olympics. Click on the thumbnail (right) to view the team – Hodgson is bottom row, far right.

Hodgson first event was the 1500 m freestyle. He wasted little time in making his presence felt. In the third heat he set a world’s record of 22:23. His entry into the finals was just three seconds slower, but still fast enough to win the semi-final heat.

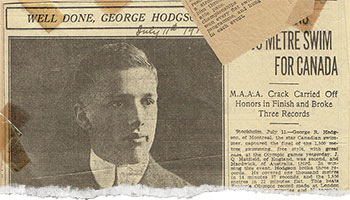

The 1500 m final was an impressive performance by the youngster with the white cap. At the first turn he was 10 m in front, after 500 m he had a lead of 25 m. The 1000 m was covered in the world’s record time of 14:37; the 1500 m in exactly 22 mins for another world’s record as well. He continued swimming to challenge the mile mark. His time of 23:45.5 was a world’s record and won a gold medal.

Commendable feats all, but they seemingly made no impression o the modest eighteen-year-old. A teammate was to recall later that “he never opened his mouth after that 1500 m swim. After he had won it he came to the house where we had our rooms and went out with the crowd for a turn around town, but the great victory was never mentioned.” Click on the thumbnail below to view a 1912 news article on the 1500 metre race.

In the sixth heat of the 400 m freestyle, Hodgson won easily again in 5:50.6. Swimming in the semi-final, he set a new world record and advanced to the 400 m finals. Hardwich of Australia and Hodgson were moving almost in unison during the early stages of the race for the gold, Hodgson slightly ahead. At the halfway mark both turned simultaneously, but the eighteen-year-olds hard training paid off. He edged ahead during the third lap; Hardwich fell behind and was taken over by the Britisher Hatfield. Hodgson finished 1.4 s ahead of Hatfield to win in the world record time of 5:24.4. His sixth world’s record; his second hold medal. His 400 m record held until 1924 when Johnny Weissmuller broke it at Amsterdam. Click on the thumbnail below to view a 1912 news article on the 400 metre race.

Homecoming

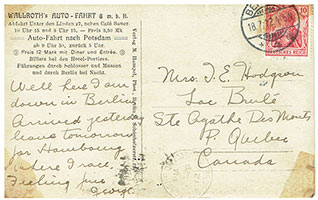

After his victories at the Olympics, Hodgson remained in Europe to compete in Germany and England, winning every event he entered. At the German championships in Hamburg, he won the Kaiser’s Cup in the 500 meter event with a time of 7 minutes 23 seconds and also competed and won the 1,500 meter event. Back in England he competed and won an exhibition race with British swimmer Taylor in Hyde Seal, near Manchester.

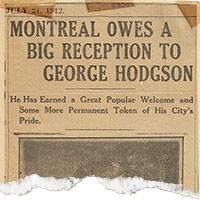

Meanwhile, back in Canada the media was reporting on how McGill University, Montreal and Canada were looking at ways to honor Hodgson upon his return in mid-August 1912. Montreal Amateur Athletics Association and the city of Montreal both began planning a reception for Hodgson, but McGill students and staff planned to get hold of Hodgson first and be at the steamer when it arrives in Montreal with a “rousing McGill yell and welcome, and a small McGill banner will be pinned to his breast by fellow students.”

Other private and official arrangements were also in the works as the media and local Montreal officials called for an event to honor Hodgson. The media reported that plans were not be made too hastily due to his very modest nature and their experiences with Hodgson when he returned from the Empire games, where he and his relatives expressed a desire that “not too much fuss” be made.

At the same time, parties from Montreal and Toronto were planning to travel to Quebec to welcome him and others back to Canada prior to his arrival in Montreal. When the steamer finally pulled into port in Quebec, Hodgson was met by his brother and together visited Chateau Frontenac, before returning to the ship to meet with a reporter for a large article in the Montreal Daily Witness. Hodgson said he enjoyed every moment of his trip and his trip back aboard the Royal George had been enjoyable with calm waters.

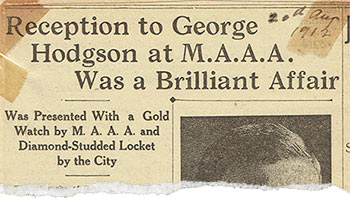

Once home in Montreal, Hodgson attended a reception held by McGill, MAAA and the city of Montreal at the clubhouse on August 20. Here, representatives that included MAAA president Gordon C. Bowie and Alderman Emard honored the champion with a gold watch and diamond-studded locket. After the formalities, Hodgson swam a hundred yards in the MAAA tank while fellow Olympian Bob Zimmerman gave an exhibition of diving from the springboard.

1913 - Hodgson's future in swimming uncertain

After returning home, Hodgson planned to spend a few months at his country home at Lake Broulet, but it wasn’t long until he was back in the pool competing.

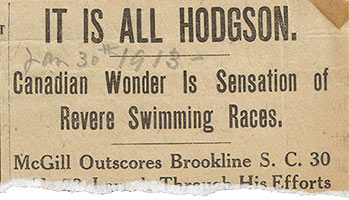

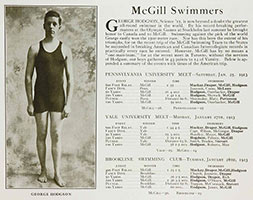

At the beginning of 1913, Hodgson joined the McGill swim team for a short tour to the U.S., including stops on Saturday evening, January 25 at the University of Pennsylvania, the following Monday night at New Haven, with Yale, and Wednesday evening with the Brookline Swimming Club of Huston. Planning of an exhibition swim to the members at the New York Athletic Club was also in the works.

Less than a week before the trip was to commence, the whole tour was put in a precarious spot when the school council, facing enormous deficits brought over from the previous year, were unable to come up with $200 needed for the trip. A notice was put in the January 20, 1913 issue of the McGill Daily asking undergraduates to pitch in to help the team come up with the funds. The students didn’t disappoint and raised the money required to keep the tour alive. Out of the three events documented, only Yale managed to beat the team from MGill, and although they just broke even through gate admissions, Hodgson and the rest of McGill left a favourable impression among the American Universities. The wins were also documented in the McGill University 1913-1914 year book.

Hodgson continued to swim through the spring and summer, including competing in the Canadian indoor swimming championships, where after winning the 440 yard championship race by 60 yards, was presented with four badges forwarded to the Canadian Amateur Swimming Association by the International Swimming Association of Europe that represented the four world records set up by Hodgson at last years Olympics.

Hodgson continued to swim through the spring and summer, including competing in the Canadian indoor swimming championships, where after winning the 440 yard championship race by 60 yards, was presented with four badges forwarded to the Canadian Amateur Swimming Association by the International Swimming Association of Europe that represented the four world records set up by Hodgson at last years Olympics.

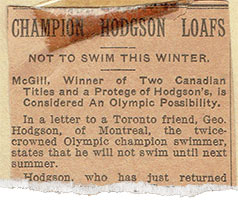

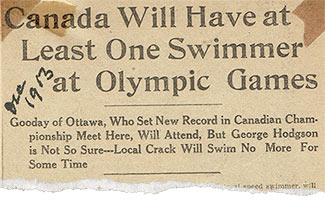

But by the summer of 2013, media had reported that Hodgson did not intend to swim that fall or winter, and possibly not until the summer of 1914. One of his last documented swim meets was annual indoor championship in December 1913.

World War I

Although George was reportedly not competing in 1914, McGill’s yearbook listed George as the Vice President of the Swimming Club for the 1914-15 year.

As the thought of war looked more likely, McGill University began to prepare for its role as far back as 1905, and by 1913 McGill’s contingent of the Canadian Officers Training Corps had 70 individuals. By the time war broke out in August 1914, McGill had over 300 volunteers.

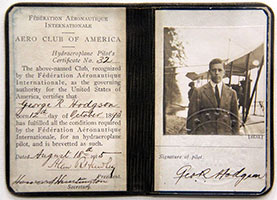

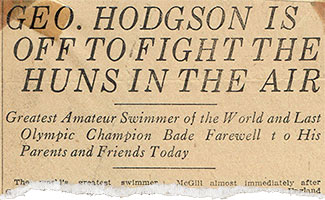

George Hodgson was one of those volunteers and left Montreal in the summer of 1915 with fellow McGill swim club member Frank McGill to the United States to qualify as a military aviator. While there, he nearly lost his life during a training flight but managed to reach ground safely.

Once he received his training as a hydraeroplane pilot, George returned to Canada and planned to finish his studies at McGill before heading off to war. But the call of duty was too strong and in the end decided to enlist in September 1915 and went overseas with the Royal Naval Air Service in January 1916.

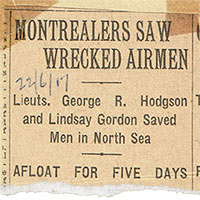

On May 29, 1917, while stationed overseas at Felixstowe based on the east coast of England, Hodgson’s team of four were flying a routine mission over the North Sea in search of German “U” boats. While heading back to base due to low clouds, they spotted, landed in rough waters and rescued two men who had been stranded on the upturned float of a seaplane for five day. For their heroic effort they were awarded the British Board of Trade Silver Medal for Lifesaving (Sea Gallantry Medal) which in due course was given to him by King George V at an investiture at Buckingham Palace. Hodgson wrote of the details of that rescue to his mother, which were then published in a news article.

Goerge remained with the Navy until 1918 when it was amalgamated with the Royal Flying Corps, and then continued with the combined body known as the Royal Air Force. During his time with the military, he was awarded the Great War Air Force Cross, the 1917 Sea Gallantry Medal (29th May 1917), British War Medal and Victory Medal.

George Hodgson - 1920 Olympics, married and a new job

After serving in the Royal Air Force, George returned home and eventually took a sales position with Greenshields & Company of Montreal in January 1920. He also decided to try out for the Olympics without much training, and although he failed to qualify for the Olympics during the trials, he was still tapped to compete in the 1920 Olympics at Antwerp, Belgium. He reminisced about the experience in a 1936 Toronto Star news article: “It was just because I won the title eight years previously. There were better men than me, but why complain? It was a nice trip.” He made it to the semi-finals in both his gold medal events. Click the thumbnail to read the full article:

On May 30, 1923 he married his first wife, Edythe Caroline Harrower (1891-1975), with which he had three children. On the eve of his marriage he was guest of honour at a banquet given for him by members of the Canadian Amateur Swimming Association. The event, which took place at the Windsor Hotel in Montreal, was hosted by CASA president Herschorn and included many of his friends and competitors.

Later that same year he was appointed Quebec sales manager at Greensheilds.

The later years

Swimming remained a part of George’s life and called it one of the finest exercises for all ages. His two sons also competed in the pool, George Junior competed at the Canadian Swimming Championships and Tom specialized in diving. In business, he continued to live in Montreal and became a senior partner in the firm of Hodgson, Roberton, Laing and Company, investment counsel.

Media interest in George and his swimming achievements have continued to garner attention throughout the years. He was inducted into the A.A.U. Hall of Fame in 1952, Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame in 1955, the International Swimming Hall of Fame in 1978, into the McGill University Sports Hall of Fame inaugural induction in 1996.